|

Books

|

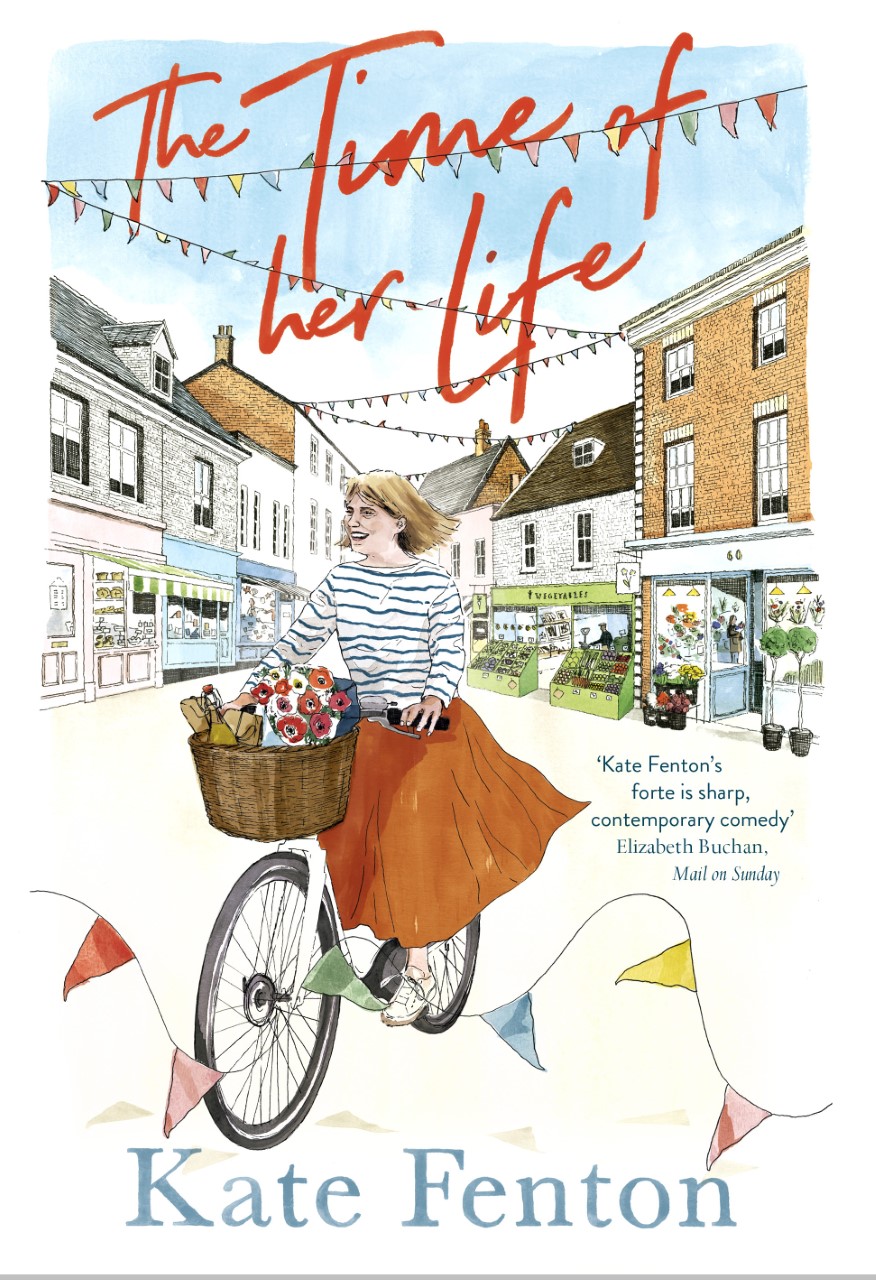

The Time of Her Life Strange times in my life So why has it taken so long to produce this merry little romantic comedy? I've got to come clean and admit to writer's block. It isn't something authors talk a lot about, in my experience. Maybe we're like the peasants living at the foot of the Transylvanian mountain who daren't even breathe the name of the count in the castle overhead. We just cross ourselves and hope the curse doesn't come our way. Well, it came my way. Big time. The black fog, if I can call it that, always lurked. I've always joked about the Dead Novel Chest into which I chucked manuscripts that had sprouted so promisingly, withered — and expired. That chest actually runs to several polythene crates now, stacked up in the attic, covered in dust, because after my last novel, Picking Up, I kept starting books. And when I say 'started' I'm talking about a couple of hundred pages or more before I felt obliged to pronounce brain death and pull the plug. You might think discarding several weeks or months' worth of work was a moment of the bleakest anguish. Curiously, I found it almost exhilarating. Perhaps, like bashing your head against a brick wall, it's joyous relief to call a halt. Plus I'm a terminal optimist. I always thought the next attempt would be better, would dance into life. However the attempts — and I barely remember the ideas and plotlines now — grew ever shorter and more widely spaced. I was embarrassed by and ashamed of my failures, grew to dread people asking (as they always do) 'when's the next one coming out?' In fairness to myself, as mentioned in the biography page, I did have less time to apply myself to the desk as my first husband, Ian, grew frail. But it certainly wasn't his fault. The problem was in me. There was one bizarre breakthrough. Don’t hold your breath. This did not prove an instant remedy, but it's one of the strangest experiences I've ever had. I'd been wandering the internet, idly Googling Writer's Block — as you would. I ran across an exercise taken from a book on the subject. In brief, you were instructed to write a dialogue with yourself. Now, when trying to explain my writing process, I've always said I felt at the mercy of two conflicting impulses. I assume right and left brain, although I can never remember which is supposed to be which. One, however, is the creative, story-spinning side which, when everything's swinging, has characters you'd never dreamed of, let alone planned, marching on to the page, spouting dialogue so fast that, when you read back, you don't recognise the words. T'other side is the rational planner, the bossy organiser who recognises that your plot is tying itself in impossible knots, points out that you've used the word 'astounded' five times in a single page, and that your heroine would have called for help on her mobile phone. Trying to harness these two impulses always felt to me like spanning two horses, one precarious foot on each, with them pulling in opposite directions. Perhaps the inventor of this dialogue exercise — one Victoria Nelson — felt the same, because she suggests writing a conversation between your rational self, and that inner creative other you. Wacky, huh? She's Californian, no surprise. Anyway, feeling a complete idiot, I decided to give it a go and… bloody hell. It was like opening a bottle in which a furious demon had been trapped these past umpteen years, who hurtled out and began hurling abuse at me. Telling me exactly how I'd ignored, inhibited, insulted and generally done my best to murder this creative other half. Six and a half thousand impassioned words poured out in one evening. Look, before you say this sounds like utter woo-woo bollocks, I agree. I promise I don't collect crystals, read auras, sense spirits, or even do yoga. I'm as four-square northern nuts and bolts as they come. I'm just telling you how it was. For me. And while the experience gave me the shock of my life, it certainly showed me I could still write. Very fast and disturbingly coherently. And, as I came to dwell on what I'd written afterwards, made me realise that I probably had let the sensible, bossy — editing — side of my brain get out of hand. That I should re-invest trust in my gut instinct. Fast forward, through widowhood, to recent times. An idea was sparking. Age was the key. The obsession with age of the (my) baby boom generation. Every bloody article on the women's pages seemed to be about pushing back the years. 'Age-appropriate' dressing. How remarkably glamorous this actress or that singer looked — for her age. Then there was the explosion in internet dating leading — allegedly — to a surge in sexually transmitted disease amongst the silver surfers. No, honestly. We oldies don't use contraception, you see. And then, a year widowed, I found myself in a new relationship and a long and happily married friend asked curiously 'what does it feel like? At our age?' My immediate answer was: it feels exactly the same at 56 as it did at 26 or even sixteen. The same exhilarating dazzle, the same roller-coaster madness. But then I thought about it a bit more. 'Except,' I said slowly, 'it's simpler. There's a certainty. You know yourself. You know what you want…' Add to that the potential for comedy in the squirming embarrassment of snowflake offspring at the very idea of sex at sixty, and a story was unfolding. Not just would this novel very deliberately focus on the romantic antics of the Senior Railcard set, I reckoned there was an offbeat parallel with Jane Austen's world of mannered courtship. Our Tinder-swiping kids may be bouncing from one bed to another as we did way back in the last century (albeit without benefit of internet) but what are the rules of the dating game for us now, at our age? We're more cautious, more reserved, scared stiff of making undignified fools of ourselves in the eyes of family and friends. We may long to find a soulmate, but we're only too aware of past mistakes. What's more, retired and prosperous, we may well be settled into a comfortable rut of old friends, family get-togethers, dinner parties and cultural pursuits. We paint watercolours, learn Italian, stitch patchwork. All in all, a leisured pattern of life which struck me as being not so very different from that of the young women and men in Austen's country gentry. Do you see where I am going? So here it is. And feisty Annie Stoneycroft sets the carousel of silver singles in her prosperous little market town spinning rather faster than she ever intended. PS: I have already written the first draft of the next novel. It is NOT in a polythene crate. |

||